The Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in German-occupied Czechoslovakia. The ghetto is quite close to Prague and you can actually take day trips to get there. The Gestapo was tasked to turn Terezín into a Jewish ghetto and concentration camp.

Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the SS, established the ghetto and directed the transportation of Czech Jews in November 1941. It held Jews from German-occupied Czechoslovakia, as well as tens of thousands of Jews deported chiefly from Germany and Austria, as well as hundreds from the Netherlands and Denmark. More than 150,000 Jews were sent there, including 15,000 children, and held there for months or years, before being sent by rail transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. Less than 150 children survived.

The Nazis intended the camp to house elderly, privileged, and famous Jews from Germany, Austria, the Czech lands, and western Europe. Conditions were harsh. At times, over 50,000 Jews lived in the space once inhabited by 7,000 Czechs. Food was scarce. About 33,000 people died at Theresienstadt, mostly due to the appalling conditions arising out of extreme population density, malnutrition and disease.

The ghetto also served as a "retirement settlement" for elderly and prominent Jews to mislead their communities about the Final Solution. It was also presented as a “model Jewish settlement” for propaganda purposes.

Ghetto inmates were only allowed to write on official postcards, and at set intervals. Postcards were written to or received from family members and friends, but could also be used as confirmation receipts for packages or permits to send packages. Receiving parcels was very important as they often included food to supplement what they received in the ghetto. The messages on the postcards had to be written in block letters in German and couldn’t exceed 30 words. Later on, the rule regarding the word limit was abolished.

The ghetto had a specific and complex postal service. The way it worked was like this:

Some of the inmates tried to contact their relatives through letters and messages that were illegally smuggled from the Theresienstadt Ghetto in order to bypass the strict censors from the “Jewish self-administration” and the SS.

Although parcels were more important to the inmates, the number of preserved postcards reveals the scale of the mail system in Theresienstadt. The content of the postcards was strictly regulated and censored.

I will end this blog post with a warning. I had the used stamp in my exhibit for many years, until I could buy a mint issue. When I had the mint issue I wanted to sell the used one, but found out that it was a forgery. How could they tell? It turns out that there are some tell-tale signs, such as the lack of a window in the cathedral.

Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the SS, established the ghetto and directed the transportation of Czech Jews in November 1941. It held Jews from German-occupied Czechoslovakia, as well as tens of thousands of Jews deported chiefly from Germany and Austria, as well as hundreds from the Netherlands and Denmark. More than 150,000 Jews were sent there, including 15,000 children, and held there for months or years, before being sent by rail transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. Less than 150 children survived.

The Nazis intended the camp to house elderly, privileged, and famous Jews from Germany, Austria, the Czech lands, and western Europe. Conditions were harsh. At times, over 50,000 Jews lived in the space once inhabited by 7,000 Czechs. Food was scarce. About 33,000 people died at Theresienstadt, mostly due to the appalling conditions arising out of extreme population density, malnutrition and disease.

The ghetto also served as a "retirement settlement" for elderly and prominent Jews to mislead their communities about the Final Solution. It was also presented as a “model Jewish settlement” for propaganda purposes.

Ghetto inmates were only allowed to write on official postcards, and at set intervals. Postcards were written to or received from family members and friends, but could also be used as confirmation receipts for packages or permits to send packages. Receiving parcels was very important as they often included food to supplement what they received in the ghetto. The messages on the postcards had to be written in block letters in German and couldn’t exceed 30 words. Later on, the rule regarding the word limit was abolished.

The ghetto had a specific and complex postal service. The way it worked was like this:

- The ghetto internee makes a request from the Jewish Council in Prague. "Send me food please"

- The Jewish Council in Prague forwards the request to the sender of the parcel, a relative, a friend, sponsor.

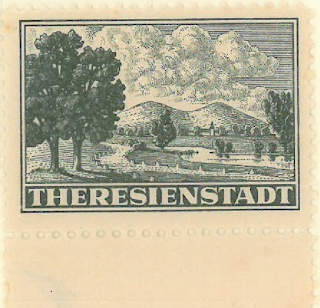

- The person who is going to send the parcel, comes in to collect the stamp (pictured here) or the stamp is sent to him.

- The sender either hands the parcel into the Jewish Council in Prague with the stamp affixed to the parcel or mails it at the post office with both the concessionary stamp on the parcel and correct postage on the waybill. Not all the senders lived in Prague.

- The parcel is then delivered to the ghetto.

- The receiver then signs a thank you card and a receipt and receives the parcel and takes it home. Food at last!

Some of the inmates tried to contact their relatives through letters and messages that were illegally smuggled from the Theresienstadt Ghetto in order to bypass the strict censors from the “Jewish self-administration” and the SS.

Although parcels were more important to the inmates, the number of preserved postcards reveals the scale of the mail system in Theresienstadt. The content of the postcards was strictly regulated and censored.

I will end this blog post with a warning. I had the used stamp in my exhibit for many years, until I could buy a mint issue. When I had the mint issue I wanted to sell the used one, but found out that it was a forgery. How could they tell? It turns out that there are some tell-tale signs, such as the lack of a window in the cathedral.

|

|

Interesting, I didn’t know these peculiarities of the postal history and the camps.

ReplyDeleteThis was an interesting camp

Deletethank you very much! very interesting and watch out from forgeries (:

ReplyDeleteGreat information, Lawrence.

ReplyDelete